There is an untruth that runs through most of our lives. And once you see it, you can’t unsee it. It’s called the myth of redemptive violence. This is the illusion that if somebody does something wrong to you, you can make it right by doing something wrong to them.

We think a corresponding act of violence will make things right. It’s a lie. We see this in movies. The bad guy does something wrong. The good guy does something wrong back. It’s like a game of Pong. Beep - beep - beep. We see it when celebrities argue on social media. We see it in our political leadership. “He said this, she said this, he said this, she said this.” And the reason it is so lethal is because no one ever learns. We get stuck in the cycle.1

There is a moment in every argument, conflict, war, revenge, where someone can put down their sword first.

You can choose to harm.

Or you can choose to heal.

Love invites us to be people who step away from harm wherever we see it. And to step into healing.

It is what we do next that matters most. Each time we are injured, we stand at the same fork in the road and choose to travel either the path of forgiveness or the path of retaliation. Even in the midst of righteous anger or rage, even if we are blinded by grief and pain, even if our suffering feels so immense and so unfair, we always make a choice. We can lash out in retaliation, demanding an eye for an eye in the false belief that, somehow, this will undo the initial harm or provide balm for our wounds. Or we can step toward the place of acceptance. We can recognize that we must give up all belief that we can change the past. The journey to acceptance begins in pain and ends in hope.2

I shared last week that one of the things that makes forgiveness a little easier is when we realize each of us are both perpetrators and victims. We harm and we are harmed. When we sit with this truth for a while, our heart can soften just a bit towards the other person. We may take down one or two bricks from the wall we’ve expertly constructed. We’ve still got work to do, but there’s enough space for some light to get in and start to do its work on us.

We’ve talked a bit about the importance of seeing the moment we choose more harm or to step onto a different path. Now let’s explore what it means to choose the path towards forgiveness and why telling the story of our pain is so important.

There’s a woman in the Bible who knew her story. She knew she hadn’t made great choices. And something inside of her compelled her to break all kinds of expectations and rules and walk into a home she had not been invited to. This woman brought the only things she knew to bring: her tears, her perfume and her love for this prophet, Jesus. She didn’t deny her story. She offered it to him.

The question could be asked of you and me today: What are we willing to bring to Love?

Maybe it’s simply the first sentence of a story you’re not sure you’re ready to uncover. Love can do something with the first sentence. Just watch.

Or maybe it’s a story you are very familiar with but it’s stayed on repeat inside your brain for decades. So much so that you don’t know any other reality. Love can do something with that story too. Love can hold it deeply and give you a new one.

Or maybe you have absolutely no idea what to bring. But you’re willing to think about it. Love can do something with that too.

Or we might be Simon, the Pharisee and host. We say the right things and do the right things but on the inside, we’re not really connected to the forgiveness offered to us. Our spiritual journey is going through the motions.

See, there’s a cost to untold stories. We think we’re avoiding pain or tension by not letting our story see the light of day. But when a story remains buried, untold, it takes on a life of its own that it was never intended to have. It gets scarier, bigger, it feels stronger than it is.

Even if intellectually we know that it is through our storytelling we will begin to heal from trauma, it is not always easy emotionally to take the first step. It can be a risky endeavor. There is the risk of being hurt again, of not being believed, of not being affirmed. But when we lock our stories inside us, the initial injury is often compounded. If we tuck our secrets and our stories away in shame or fear or silence, then we are bound to our victimhood and our trauma.3

Hear the good news today, my friends. It is not easy to tell our stories, but it is the first critical step on the path to freedom and forgiveness.

You don’t have to carry it alone anymore.

I remember the first time I told another human being I thought I was autistic. Talking on the phone with a close friend, I could feel the shame and confusion trying to silence me. It felt terrifying to open my mouth and say what I knew was most true. But the only thing that’s come from that first moment is massive freedom. I don’t have to carry the fear and uncertainty alone. I get to work it out and heal in community.

One man shares this after starting to share his story from some very painful childhood experiences: “It wasn’t as if everything was made okay by telling my secret, and I lived happily ever after,” he says. “But it was as though I had been locked in a dungeon for years, only to discover that I had the key to get out all along. I was hard on myself about that as well and regretful of all the years I had wasted. Once I joined a group of other survivors and heard their stories and shared mine, it was somehow better. Each time I talked, it was easier.”

Desmond Tutu encourages us: “Telling the story is how we get our dignity back after we have been harmed. It is how we begin to take back what was taken from us, and how we begin to understand and make meaning out of our hurting.”

So how do we tell our stories?

Telling the facts of your story is the most important element of this first step. When you tell your story, it is as if you are putting the puzzle pieces back together again, one hesitant memory at a time.

Speak the truth. Start with the facts. This step is more about the technical details of what happened. The emotions and hurt caused come in the next step.

Tell your story first to a friend, loved one, or trusted person. People must earn the right to hear your story. Don’t just tell the next person you see.

After a season, consider telling the story to the person who harmed you, or writing a letter. And it’s quite alright to not send the letter. Healing can still happen if they never know or have passed away.

Accept that whatever has happened cannot be changed or undone. Release the outcome.

Do not worry too much about how or where you tell your story. What is most important to healing is that you tell your story.

This is not a one time process. You may find that your story changes as time goes on, as you move through the forgiving process. It will change as you come to a deeper understanding of the hurt you experienced and of those who hurt you. Some have made the choice to tell their stories publicly, and they find a unique comfort in doing so.4 It is not necessary for healing to happen.

Next time, we’ll enter into the second step, naming the hurt. Friends, the path of forgiveness is about bringing our whole selves to our life. Showing up and paying attention. And letting Love heal us. This work takes courages.

Glennon Doyle says it well, “My job is not to make you comfortable by dying on the inside and staying small and quiet.” Show your whole self. This is how the resurrection begins.

To whom shall I tell my story?

Who will hear my truth

Who can open the space that my words want to fill

Who will hold open the space for the words that tumble out in fast cutting shards

And the words that stumble hesitantly into the world unsure of their welcome

Can you hold that space open for me?

Can you keep your questions and suggestions and judgments at bay

Can you wait with me for the truths that stay hidden behind my sadness, my fear, my forgetting, and my pain

Can you just hold open a space for me to tell my story?

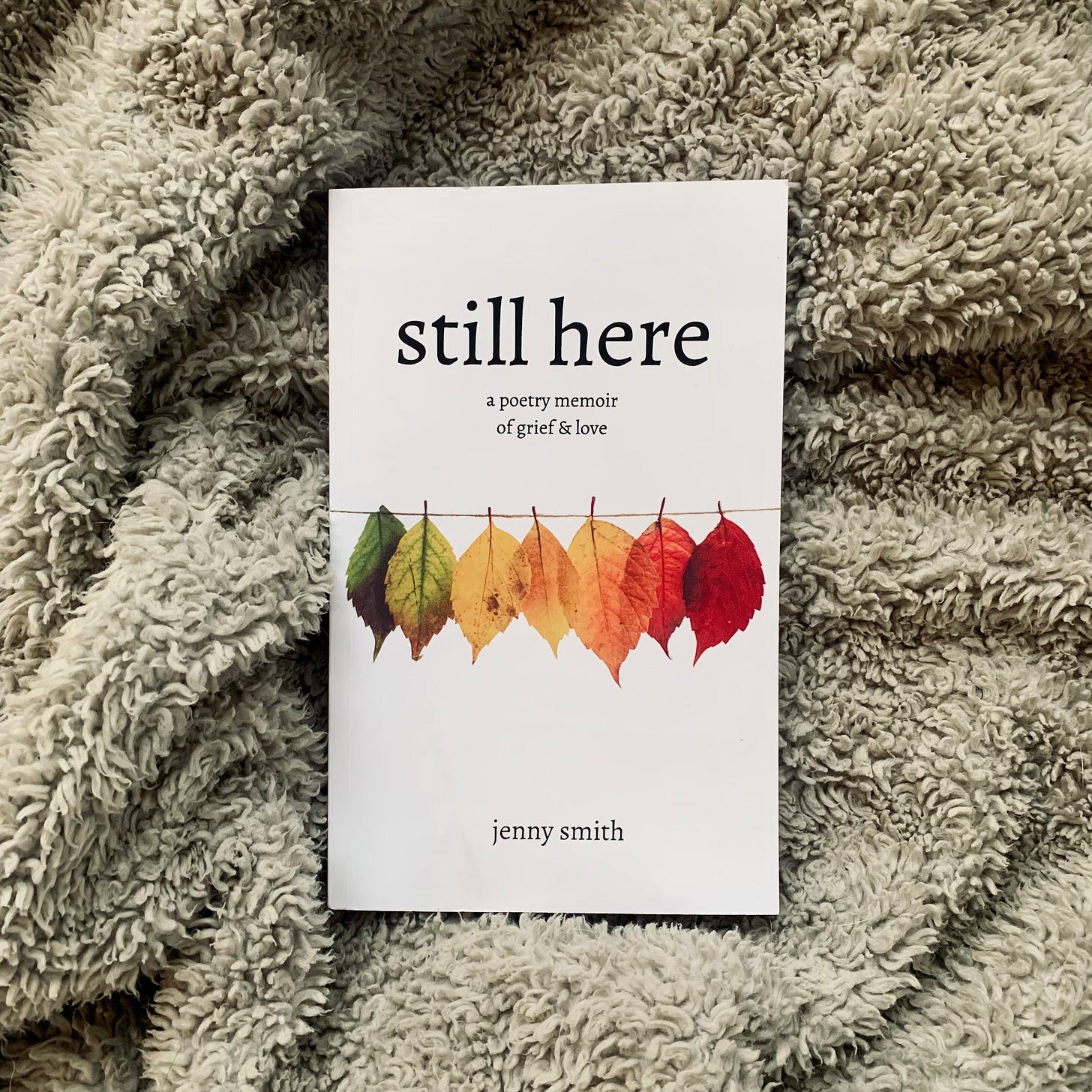

Still Here: A Poetry Memoir of Grief & Love

When faced with unexpected loss, pain and grief set up camp in our bodies and we don’t always know how to talk about what we’re experiencing, especially in the first year of loss. Still Here is a collection of poems for those trying to make sense of the fragility and terror of losing a loved one. We name the shock, wade into the everyday nuances of grief, and eventually take tentative steps into the land of the living again, only to discover love never dies. Somehow their love is still here, dancing with our every breath. Still Here is an honest reckoning with the pain and frustration of grief while journeying toward surprising healing.

Written by a poet and pastor who unexpectedly lost her youngest brother, she captures the ache of loss and the complexity of healing as her family travels the first year together. As she braves the unbearable with curiosity and trust, we’re invited to unravel the grief that awaits each of us, in the hope that love never dies.

They’re still here. So are we.

Rob Bell in one of his brilliant podcast episodes on forgiveness.

Desmond Tutu’s book “The Art of Forgiving.”

Tutu again. Such a good book.

Tutu again - for the win.

Once again, your words hit home Jenny, as I my healing journey continues. Thank you for sharing your wisdom.

Thank you, Jenny, for this powerful post.